Both technology companies and cash-strapped health and social care providers envision a future in which voice technologies, smart homes, and social robotics will enable disabled people to lead more independent lives. But how realistic are the use cases they promote?

Amazon’s 2019 advert “Morning Ritual” follows a young woman as she wakes up, makes coffee, and gets dressed. We only realize she has a visual impairment when she stands in front of a rain-spattered window and asks Alexa what the weather is like “right now” before putting on a coat and going out with her guide dog. Similarly, Amazon’s “Sharing is Caring” ad features an elderly man learning how to his Echo smart speaker to search for music and create reminders for himself. These ads promote voice technologies as empowering assistive devices, enabling elderly and disabled people to ‘overcome’ their impairments and do things independently.

The appeal of this vison of automated virtual assistants for health and social care providers is clear. Local authorities across the UK have had their budgets slashed by 49% in the last 8 years, and there are concerns about how an ageing population will impact sustainability and quality of care for vulnerable people. The Skills for Care report on AI and social robotics in social care suggests that, with extensive further research and evidence, assistive robots could provide physical, social, and cognitive support to the millions of people with unmet care needs across the UK. Indeed, local authorities are already deploying smart speakers to augment social care services, even without there being any strong evidence for their effectiveness in this context.

Our team at Loughborough and Aberdeen Universities is working with Social Action Solutions to study how disabled technology users and their (human) personal assistants use and adapt voice technologies and ‘smart home’ systems to deal with access issues in their everyday lives. Our preliminary research supports previous findings from related research on voice interfaces in everyday life, which suggest that the model of the individual ‘user’ does not work well for the social, multi-party, interactional situations in which people actually use voice technologies. When we examine the details of a real social care setting, we see how the disabled person’s independence can be generated through collaboration with their carer and the virtual assistant.

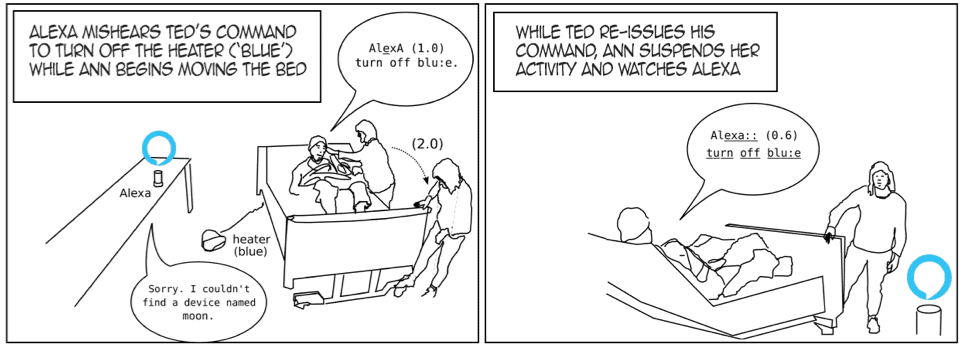

For example, in the short video clip below, Ted, who is about to be hosted out of his bed, gives a command to Alexa to turn off his heater (named ‘blue’) while his carer Ann moves around his bed, unclipping the wheel locks so she can move it underneath the ceiling track for the hoist. Before Ann can move the bed, the heater has to be off so she can shove it out of the way.

As you can see from the silences (marked by seconds in parentheses in the illustration), Ann leaves time for Ted to participate in their shared activity. Ann could have quickly switched off the heater with her foot before moving it out of the way, but instead she pauses while Ted re-does his command to Alexa – this time successfully. Here Ann is working with Ted, who is working with Alexa. By pausing and waiting for him to finish his part of the action, Ann supports his independent action within their joint, interdependent sequence of actions.

This simple example suggests how a disabled person’s independence may not conform to the model of an individual user. Instead, it suggests that to enhance someone’s independence, voice technologies should be designed to support everyone’s role within collaborative, shared actions. Over the next few years, our research will involve building collections of thousands of similar cases, exploring how everyday care tasks such as getting out of bed, getting dressed, and eating all involve similar sequences of joint action. The ultimate goal is to understand, in detail, how these activities work in practice, how they break down when things go wrong, and how to design voice technologies alongside training and policy to enhance disabled people’s independent living in ways that support the interdependent capabilities of the whole team.

You can follow project as it develops by checking Saul Albert’s blog or following him @saul on twitter. You can also support the project by voting for it in the 2020 CALIBRE awards, where it is one of six finalists for championing equality, diversity and inclusion in research at Loughborough University.